Observations on the Adverse Impact of TANF After 20 Years

By Marc Cohan, Executive Director, National Center for Law and Economic Justice

Twenty years ago then President Clinton signed the so-called “welfare reform” law. The legislation was a comprehensive and far-reaching effort to eliminate welfare as this nation had known it since the Great Depression and to radically redefine the manner in which our society addresses family poverty.

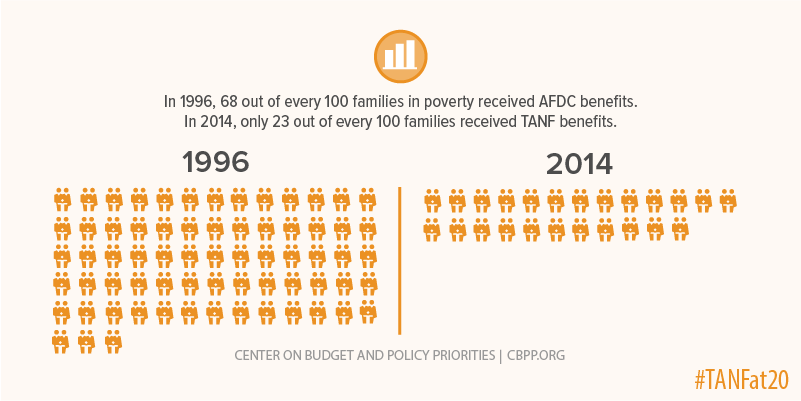

The centerpiece of “welfare reform” is the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) block grant. TANF replaced the federal Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, which had assured cash assistance to America’s neediest families since 1935, with a block grant to the states.

How TANF Fails as a Safety Net

Key features of the TANF block grant undermine its ability to be an effective safety net program. The law provides fixed federal funding to the states, which has eroded in value over the years. The block grant also imposes lifetime limits on TANF assistance of no more than five years – yet, many states have chosen even shorter lifetime limits. Arkansas, Idaho, and Indiana have 24 month time limits. And, Arizona leads the nation with a 12 month time limit!

TANF emphasizes work requirements but has failed to offer true work opportunities to parents. Adult TANF recipients, with some exceptions, must participate in work activities as a condition of receiving cash benefits. Yet, these activities emphasize “make work” workfare and similar programs over real education and training that actually help move TANF parents into living wage jobs. Only one percent of TANF dollars nationwide support education and training, while some states spend no TANF dollars on vocational education. Without programs that provide job skills and basic training, families are condemned to a cycle of poverty.

The block grant funding structure makes it impossible for TANF to respond to the cyclical nature of poverty and changes in the broader economy. Study after study shows that the need for assistance correlates strongly with the job market. As would be expected, as jobs become more plentiful, applications for assistance decline. Yet, as the Great Recession showed, fixed federal block grants mean that there are no additional funds to meet increased need when the economy lags. Moreover, TANF benefits, which are set by each state, are actually worth much less than when TANF was enacted, and are far below the poverty level.

TANF vests enormous discretion in the states as to how the TANF funds are spent, allowing states to divert TANF funds to purposes other than cash assistance for families. The Center on Budget Policies and Priorities (CBPP) has observed that, under the TANF block grant, the percent of funding spent on basic cash assistance for poor families had plummeted from 70% to 26% by 2014. Further, ten states spend less than 10% of their TANF budget on cash assistance, which allows families to pay for items such as housing, clothing, food, and other essentials.

TANF also gives states vast discretion in designing and administering their TANF programs and there is disturbing evidence of a disproportionate negative impact on racial minorities. Research has shown that the larger the black proportion of a state’s caseload, the greater the decline in the proportion of poor children who received TANF benefits.

TANF’s Failure to Serve Families in Poverty

In the early 1990s, 5.1 million families were receiving AFDC assistance. By the time TANF was enacted in August 1996, the number had fallen to 4.4 million families. By September 2000, only 2.2 million families were receiving ongoing TANF assistance. The impact is even more troubling when one views how TANF performed during the worst recession since the Great Depression. As CBPP has reported, in almost half the states, the number of TANF cases barely changed during the recession and it actually decreased in six states.

Image courtesy of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Moreover, the impact on children has been particularly brutal. As CBPP reports, under AFDC, almost two out of every three poor children were lifted out of deep poverty. Under TANF, that figure is reduced to one in five poor children being lifted out of deep poverty. The consequences reverberate throughout a child’s lifetime, leading to poorer performance in school and significantly reduced lifetime earnings.

NCLEJ’s Advocacy for a Better TANF Program

Yet, for all of its troubling features, TANF remains a vital remnant of a safety net for many of our nation’s poorest. Almost one half of all TANF cases provide assistance to children-only cases, because these children often live with a relative other than a parent. In yet other households, the parent is a person with a disability who cannot earn enough to provide for her family.

NCLEJ has applied impact litigation and policy advocacy, and has partnered with low-income communities and advocates across the country to fight for fundamental fairness in the administration of TANF and other safety net programs. NCLEJ’s work in this area is not a recognition that TANF is a worthy program – it is not. Rather, it is a recognition that until it is replaced with a program that unequivocally meets the needs of children and families, we must continue to preserve even these most tattered remnants of a safety net.

Since the passage of TANF, we have secured important victories. We beat back efforts to prevent families from applying for TANF. We successfully challenged policies that required TANF recipients to work in in unsafe conditions and subjected them to racial and sexual harassment. We reversed a program that unfairly sanctioned mothers who could not comply with TANF rules through no fault of their own.

Our work with colleagues has helped prevent the state from reducing the woefully inadequate TANF grant even further simply because one of the family’s children receives disability benefits. We joined colleagues in protecting the right of TANF recipients to have an administrative fair hearing before their benefits could be cut. We partnered with other groups to ensure that applicants for TANF are screened to identify hidden disabilities, such as cognitive and psychiatric impairments, and receive necessary accommodations to help them navigate the TANF bureaucracy.

We also helped community organizers in their efforts to provide a stronger, more organized voice for low-income families across the country. Our ground-breaking project provided support for organizing with 21st Century technology tools and strategic assistance. In New York, Ohio, Montana, West Virginia, Texas, and many other states, community-based organizers succeeded in lessening the impact of the harshest policies and fought successfully to expand opportunities for low-income families, many of which are headed by women of color.

NCLEJ’s Vision for a Better, More Just Future

As we look forward, a return to the flawed AFDC program of the past should not be our end-game. Rather, we must continue to work toward a future where basic income support is a guaranteed right for all. Our vision is a country that invests in children by ensuring that that they have adequate income, which is critical for their health and ability to succeed in school, as well as later in the workplace. Our vision is a country that promotes the full inclusion of people with disabilities and racial and ethnic minorities, and provides work opportunities for those who need them.

We will continue the struggle to ensure the preservation and expansion of basic safety net programs and the fair treatment of all in an economy that does not provide living wage jobs for all; does not provide a universal right to health care and housing; does not provide decent education for all; and does not guarantee child care. This struggle is daunting, but it has been and will continue to be NCLEJ’s mission, and we hope you will continue to fight alongside us.